Geology

When you walk in the BWT land you can touch and examine 120-million-year-old fossils, which once formed an oyster bed in a subtropical, shallow Lower Cretaceous sea.

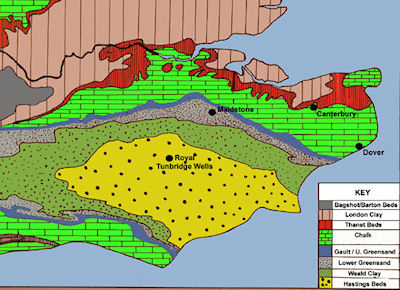

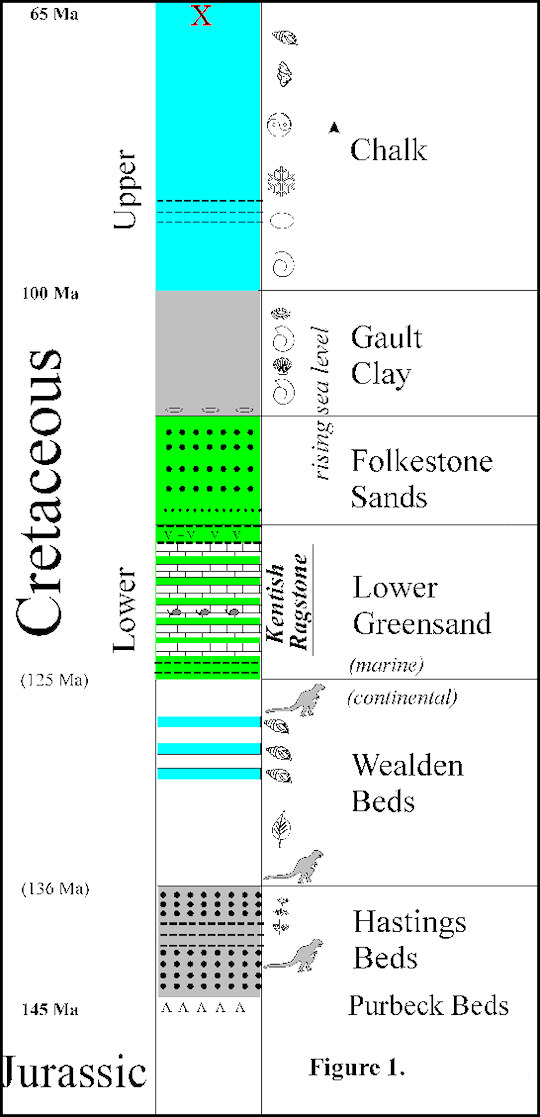

During the Lower Cretaceous (145–100 million years ago) dinosaurs were still roaming the continents, particularly the vegetated plains of the Weald of Kent.

When you visit us please confine your geological examination to the limestone blocks on the flat grassy areas and do not climb the bank below the outcrop, near the boundary fence with the angling club.

The best block to examine is located behind the tree sponsored by Richard & Ann Lemon.

In the interests of geoconservation, please do not hammer or remove large specimens from this important locality, which could possibly be designated as a Regionally Important Geological Site (RIGS) in the future.

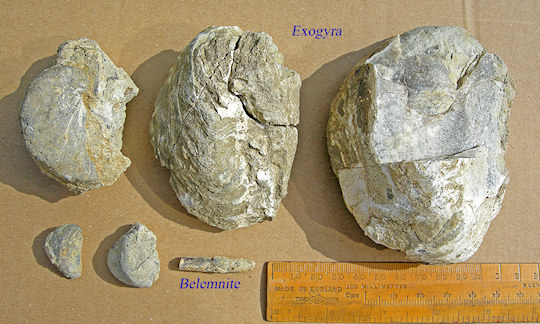

This photograph shows fossils which you may see in the Kentish ragstone which was uncovered with excavations for the new paths and the bridge across the Lilk stream. Bearsted resident Dr Gareth George, retired lecturer in Geology at the University of Greenwich, author of "The Geology of South Wales" and member of the Kent Regionally Important Geological Sites Group Committee has written this article about the geology of the BWT land.

These interesting fossilized oysters, found in a rock known as the Kentish Ragstone, have come to light as a result of recent work providing the new paths and the bridge across the Lilk stream. The fossil bed can be seen in an exposure on the west side of the valley, above the bridge and below the new path (10 metres left of the bench dedicated to Rod Freear) and in isolated blocks of limestone located on the grassy platform. The limestone is composed almost entirely of the remains of an extinct oyster known by its Latin name Exogyra, a fossil related to Gryphaea (commonly known as the ‘Devil’s toenail’).

Individual specimens within the bed vary in size from a couple of centimetres to large forms up to 15 cm in length (see photograph above). Some of the shells are in their original life position (flat side up), but others have been moved as a result of strong currents active during the formation of the oyster bank. The thick shells of the larger specimens have many layers and encrustations (just like modern oysters), indicating yearly growth over decades in a warm, wave-washed shallow sea. You can also find the occasional remains of other fossils such as torpedo-shaped belemnites (‘thunderbolts’), bivalves, shell debris, and burrows left by invertebrates that lived within the sediment. Closer examination of the limestone with a magnifying glass or hand lens shows that it contains grains of sand (quartz) and also a greenish-black mineral called glauconite, which gives the strata the name Greensand.

Ragstone has been an important building stone in Kent since Roman times and stone quarried in the Maidstone area was used in the construction of the Tower of London, Rochester Castle, Knole House, Ightham Mote, the Archbishops’ Palace, Maidstone Prison and many other historic buildings and churches (including All Saints and the Holy Cross).

The term ragstone was coined by the old quarrymen, due to the fact the rock broke along ragged surfaces when being dressed.

Typically the hard limestones are interbedded with softer silty and sandy rock known as hassock, hence the term ‘rag and hassock’. In 1834 the famous palaeontologist Gideon Mantell (1790–1852), who was born in Lewes, described a unique fossil Iguanodon from a ragstone quarry formerly located in Queens Road, Maidstone (Bensted’s Quarry, later renamed Iguanodon Quarry). Since the iguanodons were herbivores, this dinosaur must have been washed out to sea from its feeding grounds on the coastal plain, which was located along what is now the North Downs (an area known geologically as the London Platform). The original specimen containing the dinosaur bones is now housed in the Natural History Museum (London), but a cast, known as the ‘Mantell-Piece’, previously at Maidstone Museum, is now on display at Hastings Museum.

In 1949 an Iguanodon was incorporated into the Maidstone Coat of Arms. In the 1940s there were more than a dozen ragstone quarries in Kent producing road- and building-stone (e.g. Borough Green, Ditton, Quarry Hill Aylesford, Allington, West Farleigh, Loose, Boughton, Little Chart), but today the only one still working is Gallagher’s Hermitage Quarry at Barming.

Other interesting geological features relating to the Bearsted and the Weald of Kent are summarized in the geological time scale above.

White silica sand, used for glass production, was worked around the mid 1800s in small galleries adjacent to the dressage training area on Miss Moore’s riding school field, and also near Birling House.

Records from 1856 indicate that around 1000 tons of glass sand was being produced annually from pits in the Aylesford–Bearsted–Hollingbourne area.

Fullers Earth, a very pure clay used for fulling (degreasing and cleansing) wool, was previously worked from pits in the Vinters–Grove Green area.

During the early 1900s there was a brick factory (Bearsted Brick and Tile Works, closed around 1926) just west of the allotments, adjacent to Bearsted Golf Club (see the sketch map on Page 5 in: "Bearsted and Thurnham Remembered" by Kathryn Kersey).

The bricks, made from locally extracted Gault Clay, were reddish-brown with a very open texture, and no indentation (frog) to hold mortar. Samples of these bricks can still be found in the undergrowth. The tiles were made for a mixture of clay and sand dug from a pit located on the golf course. In the 1920s an assemblage of ammonites collected from the Bearsted clay pit were used to date the Gault Clay and these important specimens were subsequently donated to the British Geological Survey.